Patient Resources

Get Healthy!

Archaeologists Discover Evidence of Surgical Amputation Performed 30,000 Years Ago

- September 12, 2022

- Cara Murez

- HealthDay Reporter

Skeletal remains of a young adult discovered in a remote cave in Borneo appear to be the oldest known case of surgical amputation.

Australian and Indonesian researchers estimate the bones are at least 31,000 years old. It appears that the young adult lost his foot and lower leg in childhood and lived for at least six to nine more years after that, they said.

"The discovery implies that at least some modern human foraging groups in tropical Asia had developed sophisticated medical knowledge and skills long before the Neolithic farming transition," said co-lead researcher Melandri Vlok. She's a bioarchaeologist and expert in ancient skeletons at the University of Sydney.

In a university news release, Vlok called the find "incredibly exciting and unexpected."

Even with modern medicine, preventing infections after amputation is hard, making the ability to do so tens of thousands of years ago a remarkable feat. Amputation requires working with veins, arteries, nerve, tissue and more, while keeping the wound clean.

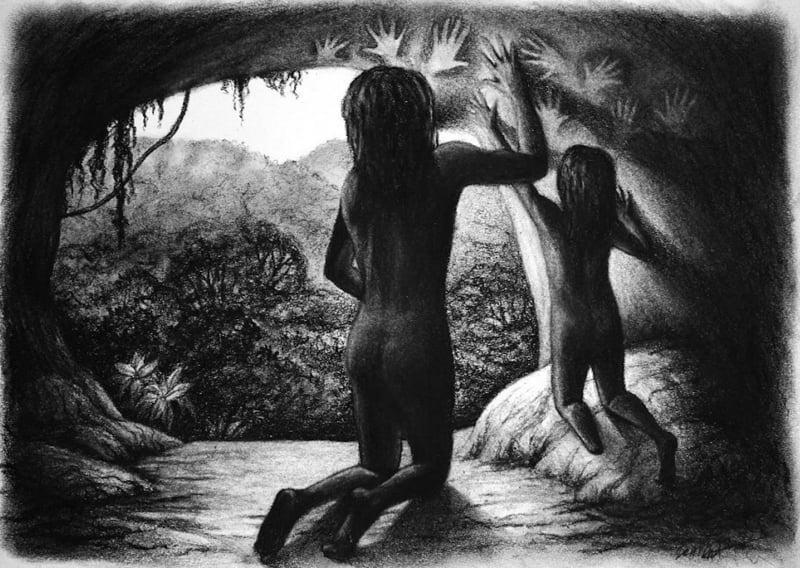

What eventually caused the young adult's death is unknown. The body was carefully buried in the Liang Tebo cave in Indonesia's East Kalimantan province. The cave is in an area on the island of Borneo that contains some of the world's earliest dated rock art.

Archaeologists from Griffith University in Australia and the University of Western Australia recovered the remains days before borders closed for the COVID pandemic in March 2020. The team, which also included representation from the Kalimantan Timur Cultural Heritage Preservation Center, invited Vlok to study the bones in Australia.

"No one told me they had not found the left foot in the grave," she said. "They kept it hidden from me to see what I would find."

The left leg of the remains looked withered and was the size of a child's, but the individual was an adult. When Vlok unwrapped the part of the leg that contained the stump, the cut was clean, well-healed and had no evidence of any infection.

"The chances the amputation was an accident was so infinitely small," she said. "The only conclusion was this was stone-age surgery."

When Vlok told colleagues what she found, they told her they already knew the foot was missing from the grave.

The skeleton also had evidence of a well-healed neck fracture and trauma to the collarbone. That may have occurred at the same time, Vlok said.

"An accident, such as a rock fall may have caused the injuries, and it was clearly recognized by the community that the foot had to be taken off for the child to survive," she said.

Co-researcher Maxime Aubert of Griffith University noted that the area is "extremely rugged" with steep mountains and caves.

To reach the cave, archaeologists needed to kayak into the valley and scale an enormous cliff. They said it was remarkable for someone with one leg to have survived in such challenging terrain.

"This unique find challenges assumptions of humanity's capabilities in the past and is set to significantly advance our understanding of human lifeways in tropical rainforests," said co-researcher India Dilkes-Hall of the University of Western Australia.

The findings were published Sept. 7 in the journal Nature.

More information

The U.S. Bureau of Land Management shares another story on the discovery of ancient bones.

SOURCE: University of Sydney, news release, Sept. 7, 2022